A New Hebrew Textbook

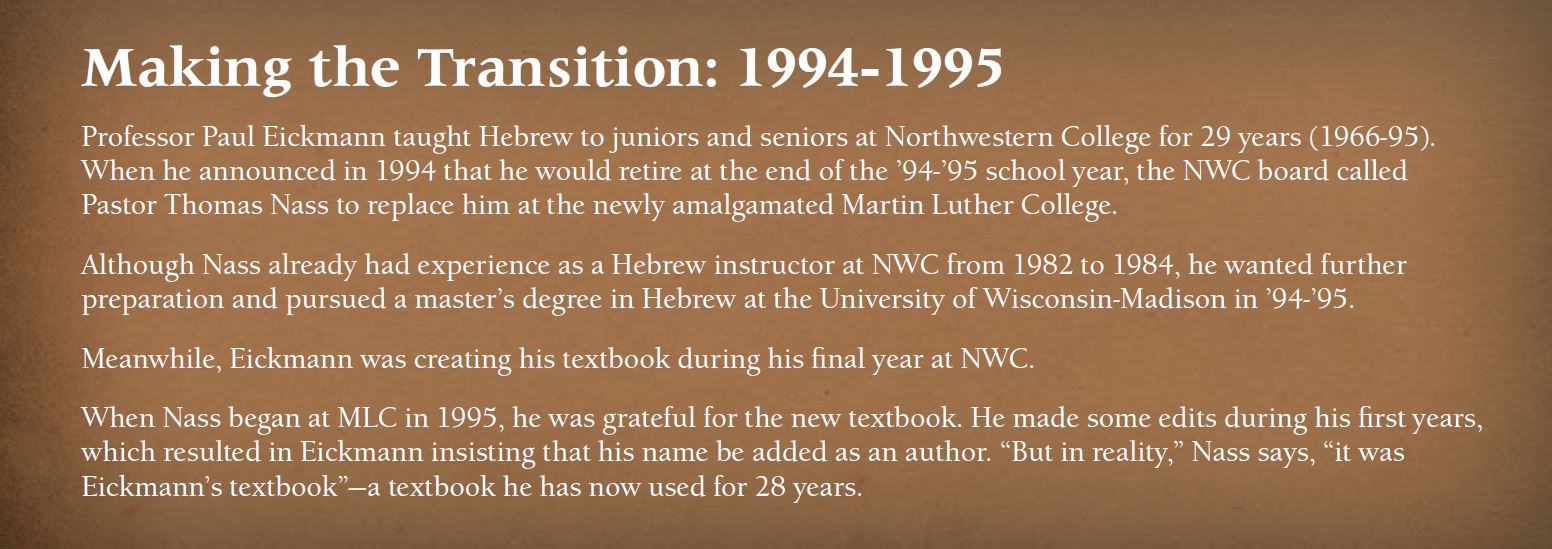

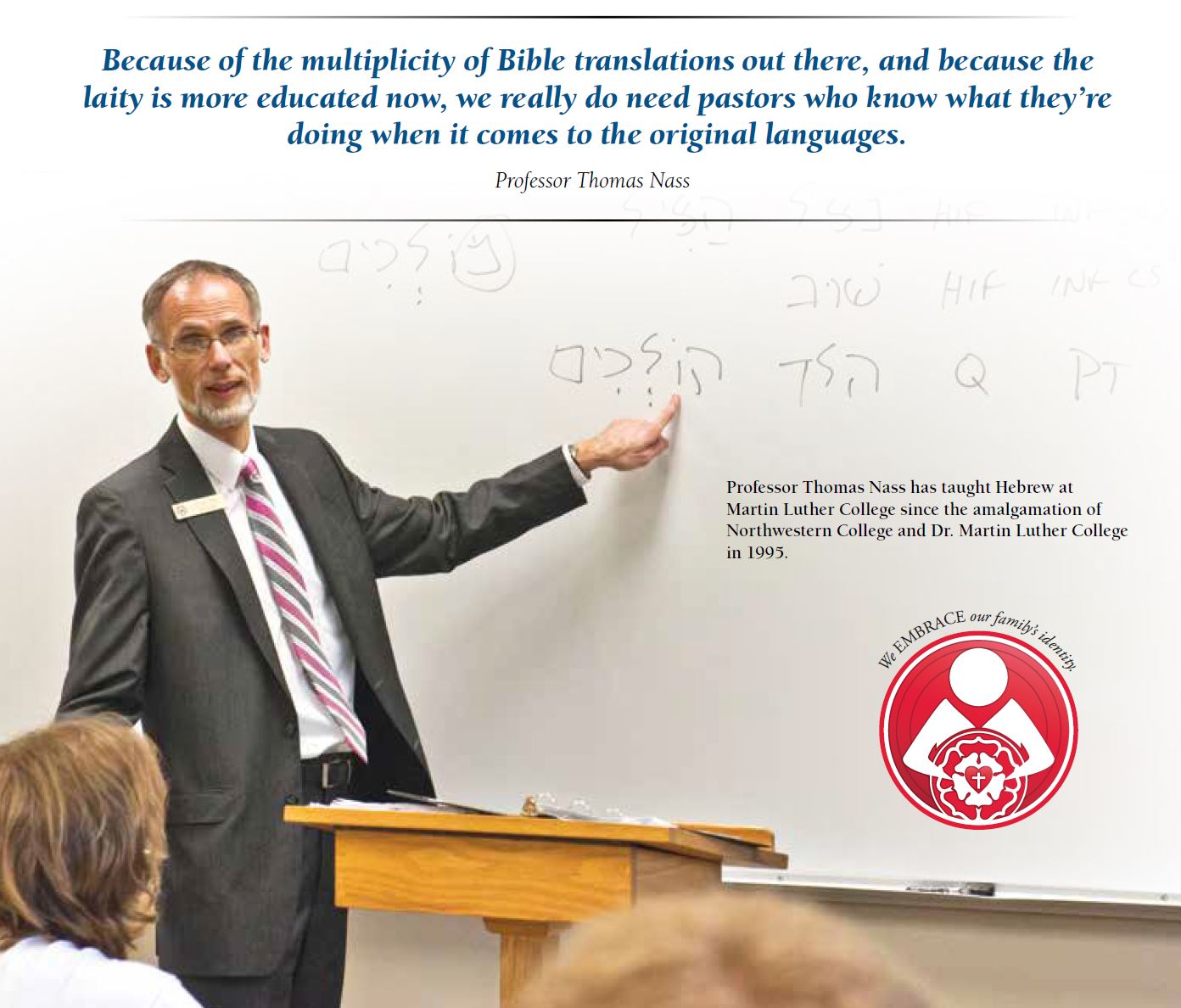

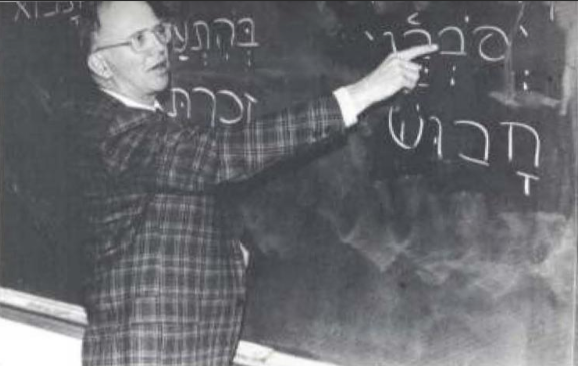

They are the first words in Genesis, the first words in the Bible, and the first words that junior preseminary students at Martin Luther College sink their teeth into—in Hebrew. Professor Thomas Nass NWC ’77, WLS ’82 (pictured right), is the one who opens the wonders of the Hebrew language to these young men.

They are the first words in Genesis, the first words in the Bible, and the first words that junior preseminary students at Martin Luther College sink their teeth into—in Hebrew. Professor Thomas Nass NWC ’77, WLS ’82 (pictured right), is the one who opens the wonders of the Hebrew language to these young men.

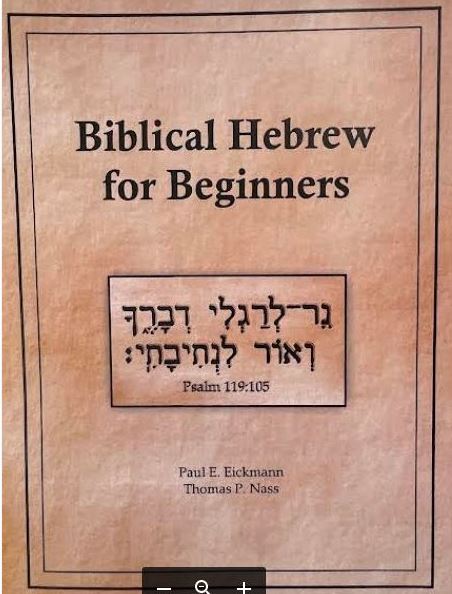

Since 1995, Nass has been using Biblical Hebrew for Beginners, a textbook written by his predecessor, Northwestern College Professor Paul Eickmann, in 1994-1995, the last year before the amalgamation resulting in Martin Luther College.

A student named Jonathan Schroeder NWC ’95, WLS ’99, now pastor at Faith-Sharpsburg, Georgia, was tasked with typing the Eickmann tome.

A student named Jonathan Schroeder NWC ’95, WLS ’99, now pastor at Faith-Sharpsburg, Georgia, was tasked with typing the Eickmann tome.

The 1995 textbook has served WELS preseminary men well, but now it’s time for a new beginning. Professor Nass is revising and republishing the book as Reading Biblical Hebrew.

“I’m not going to be around forever,” he says. “Someone is going to come and replace me. Professor Eickmann’s book is in a word processing program that’s not even around anymore, so I thought it would be kind to put the textbook into Microsoft Word, so that the next Hebrew professor can do what he wants with it. Plus, I can add improvements that I have come upon in the last 28 years.”

The college received an Antioch Grant for the project, which enabled Nass to hire a preseminary senior named Calvin Arstein (Cross of Christ-Boise ID) to type the book. Like Pastor Jonathan Schroeder, Calvin’s talents match the task. “Calvin is perfect for this project,” Nass says. “A wonderful gift from God.”

The college received an Antioch Grant for the project, which enabled Nass to hire a preseminary senior named Calvin Arstein (Cross of Christ-Boise ID) to type the book. Like Pastor Jonathan Schroeder, Calvin’s talents match the task. “Calvin is perfect for this project,” Nass says. “A wonderful gift from God.”

Nass also gives a shout-out to the current MLC juniors, who are enduring the first working draft of the revision, and to Dr. Mark Paustian, who is teaching additional sections of Hebrew this year to give him more time to work on the textbook.

Why do we need to create our own textbook? Almost every major academic publishing house markets a biblical Hebrew textbook. In fact, Eickmann used Weingreen’s text (Oxford University Press) for years before he wrote his own. But Nass explains that a few components are significantly better in Eickmann’s—and now his own—approach to teaching Hebrew.

Why do we need to create our own textbook? Almost every major academic publishing house markets a biblical Hebrew textbook. In fact, Eickmann used Weingreen’s text (Oxford University Press) for years before he wrote his own. But Nass explains that a few components are significantly better in Eickmann’s—and now his own—approach to teaching Hebrew.

First, the grammar presentation is simpler in Eickmann/Nass than in some other books. “It’s just enough for the beginning student. I think that some textbooks include too much detail right away, and that can overwhelm the beginning student.”

Second, Eickmann presents the Hebrew verb differently in his text. “The verb is complicated in Hebrew,” Nass says, “and Eickmann found a well-organized and manageable way to teach it.”

Second, Eickmann presents the Hebrew verb differently in his text. “The verb is complicated in Hebrew,” Nass says, “and Eickmann found a well-organized and manageable way to teach it.”

And third, Eickmann incorporated simplified Hebrew Bible stories early on. “Other texts do not do this,” Nass says. “They’ll use illustrative sentences but not whole stories from the Bible.” Already in lesson 12 of Eickmann’s book, students are reading the creation story.

Nass has added even more stories in his revision. Every other lesson begins with a story, focusing on great Old Testament leaders like Abraham, Moses, Joshua, Elisha, Ezekiel, and David. “Our primary goal is to read stories from the Bible, not learn Hebrew grammar,” he says. “We do learn the grammar, but we do it to support the reading and understanding of the Bible story. That’s why this text is called Reading Biblical Hebrew.”

Nass feels that these particulars in the Eickmann/Nass textbooks make the study of Hebrew more enjoyable. “Those components have made first-year Hebrew something most students like better than they would with other texts. They’d be blown away by the amount of detail in some of the other books. It’s been a more enjoyable experience with our text.”

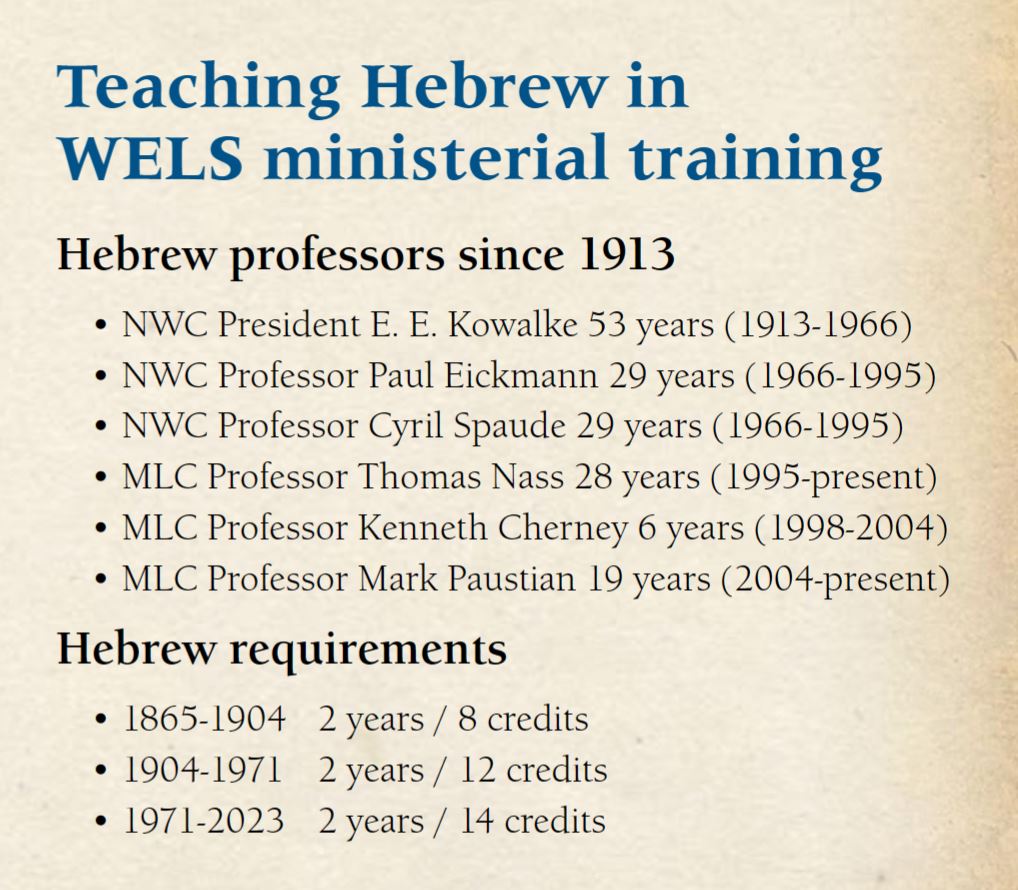

Some things will not change: Although the textbook will be different next year, the requirement that preseminary men learn Hebrew will not change. For more than a century—and for the foreseeable future—preseminary men in WELS have studied Greek all four years and Hebrew their junior and senior years. Then they have built on these skills at Wisconsin Lutheran Seminary.

Some things will not change: Although the textbook will be different next year, the requirement that preseminary men learn Hebrew will not change. For more than a century—and for the foreseeable future—preseminary men in WELS have studied Greek all four years and Hebrew their junior and senior years. Then they have built on these skills at Wisconsin Lutheran Seminary.

Nass thinks that’s just as it should be. In fact, learning Greek and Hebrew may be more important now than ever, he says.

“Because of the multiplicity of Bible translations out there, and because the laity is more educated now, we really do need pastors who know what they’re doing when it comes to the original languages.”

He adds, “One thing I always say to students is this: Certainly, you can preach a sermon not knowing Hebrew, but you can be a more careful preacher—and a more confident preacher and teacher—if you’ve studied the original languages.”